In this article, which is Part 2 of “What is Design,” I’m excited to dive into the value of design and what it truly means for us and our everyday lives. I’ll share some concrete examples of how design plays a role in shaping the world around us, and I’ll also pose an important question: “Should we value design more? Does it really make a difference?” It’s a 10-minute read. I hope you enjoy it!

If you prefer to listen, this is a”deep-dive” podcast version of the post with two AI hosts – it’s amazing! (about 14 minutes)

Does design have value?

The question of whether design as a profession adds value to our work and lives has sparked considerable academic discussion over the years.

There are some major studies that have tracked publicly listed companies over five and ten-year periods that found something quite remarkable: those companies embracing design in their business strategies make more than double the profits compared to their competitors. Isn’t that amazing?

It’s clear that design plays a significant role, and it has obvious value in achieving those results.

Yet, many people in management and leadership positions still don’t recognise the value of “design” or the economic benefits it could bring to their organisations.

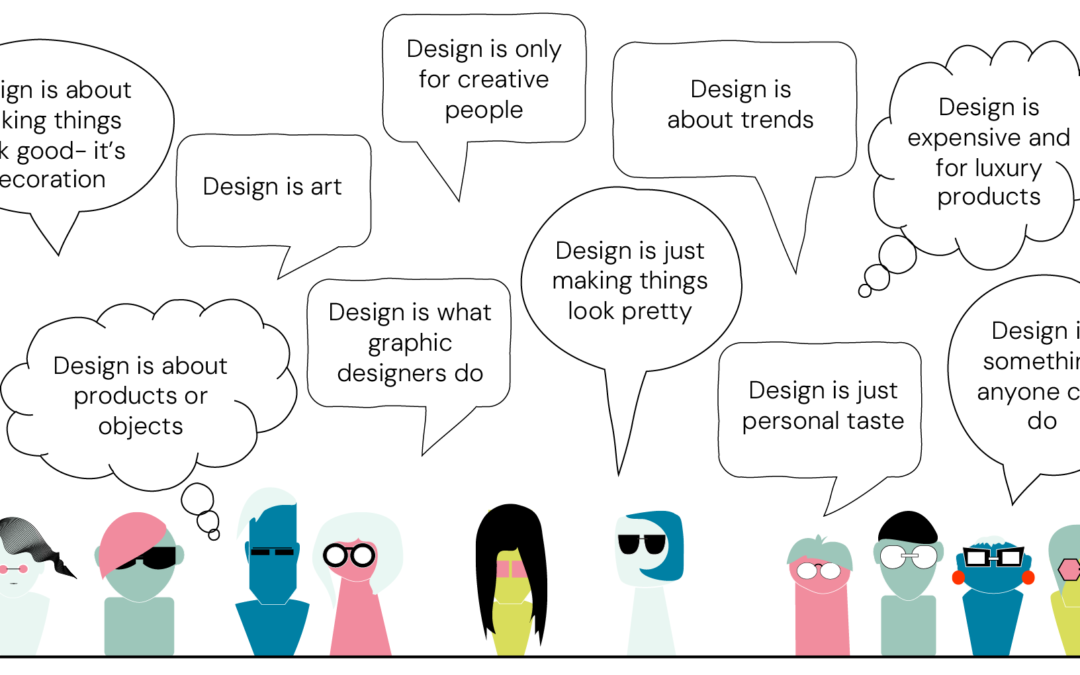

Why isn’t design appreciated?

Looking at those results, “design” definitely deserves more appreciation. However, perhaps the reason it doesn’t receive it is because design lacks a universally agreed-upon definition.

Research also shows us that when we are unsure of something, we tend to be less inclined to engage with it.

John Heskett, a renowned British writer and lecturer, gives a profound explanation of why we might not value design when he states that “The meaning of design is rather like the word ‘love’, the meaning of which radically shifts dependent upon who is using it, to whom it is applied, and in what context.”

In other words, each of us is responsible for our own meaning of design.

Perhaps the best way to assess the value of design is by observing how it is used.

Design is a human endeavour.

We can certainly say that design is an inherent part of being human. Ever since the beginning of time, we’ve been planning, shaping, and creating the world around us to suit our lives. It’s incredible to think about.

Take, for example, the image below, which shows stencilled handprints found in a cave that is approximately 9,000 years old.

I find it fascinating that most of these stencils depict human left hands. While we may never figure out the exact reason behind this fact, historians believe they were created by blowing coloured pigments through a hollow tube held in the right hand. Makes so much sense!

Don’t you think it’s remarkable that they “designed” a message that has endured for 9,000 years?

Cueva de las Manos, Perito Moreno, Argentina. The art in the cave is dated between 7,300 BC and 700 AD; stencilled, mostly left-hand images are shown. Source: Cave painting. (2024, May 5). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cave_painting

So, fundamentally, we design where and how we spend our time and with whom we interact. Our human ability to think and communicate with others leads to more design outcomes.

We might not want to be designers, we might not care about design, but we can all design.

Look around you, study your environment, and examine what you are doing. Take a moment to observe your chair, door, window, laptop, books, papers, and any other items.

Think about the fact that someone, a person or group of people, somewhere, designed how these items would not only look and feel but also function, be made, and, of course, reach us and improve our lives. All of that is design.

Design is impartial

When it comes to design, we also need to think about this.

We “design” clothes and buildings to protect us, and we also “design” guns so we can kill each other. Pretty confronting, isn’t it, when we think of it like that?

Design itself is neither inherently good nor bad; rather, the outcomes of our designs can have positive or negative effects on humanity.

An example of this is the design of plastic products.

Today, plastic causes severe problems for the planet only because we failed to consider its impact on the environment it was initially designed to help.

Reinhold Möller Ermell, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

This presents us with an important lesson: we must evaluate the value of design to understand how our choices impact the world around us.

Sir Winston Churchill—A Design Advocate

Interestingly, people who value design can be found in some unexpected places.

Originally named the Council of Industrial Design (“The Council”), it was established by Winston Churchill’s wartime government in 1944, before the end of World War II.

Yes, that Winston Churchill!

I was amazed and impressed when I first heard of his vision and support for design.

The Council’s mission was clear: to revitalise the economy after the war by promoting the design of British-made products.

Winston Churchill and his Chiefs of Staff around a conference table aboard SS QUEEN MARY en route to the USA, May 1943.

Churchill’s visionary move underscored the value of design for Britain and its post-war economy.

Today, more than 80 years after the war, the renamed Design Council is a globally respected organisation that continues to promote design for the betterment of society.

The “Council’s” approach towards design is telling. They have a very clear definition of design that clearly shows how highly they value it: “Design is what happens when people use creativity to solve problems. Computers and coffee cups, skyscrapers and socks. Everything not made by nature, has been designed.”

Below is a short video by the Design Council explaining the value of design (1:30 min).

Source: https://youtu.be/AMp7OinIJd8

Wow, “Everything not made by nature has been designed.” That’s a powerful statement, for sure. Have you ever thought about design like that?

Yet, this also raises the question of how we design AI.

Humans are at a design crossroads

Right now, we’re all adjusting to a new reality with AI. I feel it’s essential to remember that AI itself is neither inherently good nor bad; it’s ultimately up to us to decide how we utilise it.

This is an ideal time to reflect on what it means to be human and to ensure that the design of AI works in our favour.

We can make a difference by just considering how we use AI tools.

Are we thoughtful and mindful in all our interactions with it? Are we making an effort to understand its limitations and the potential biases that may come with our interactions?

Yes, we can make a difference in the outcome.

We are all involved in the design of AI, so our input will make a difference to the outcome. For instance, we can protect our privacy by ensuring that passwords are secure. We can keep our software up-to-date. We can be “discerning” about what data we share and which AI platforms we use!

Looking ahead, the future of design will require us to have a deeper understanding of what people truly need, what frustrates us and others, how we behave, and what our goals are.

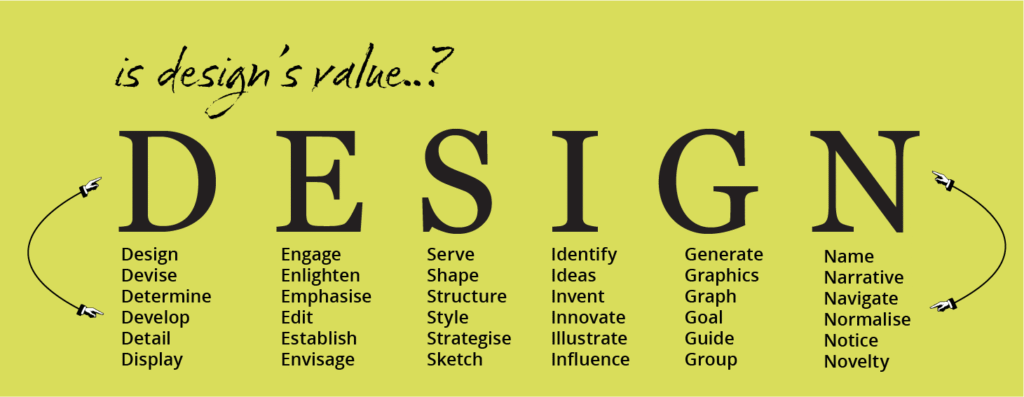

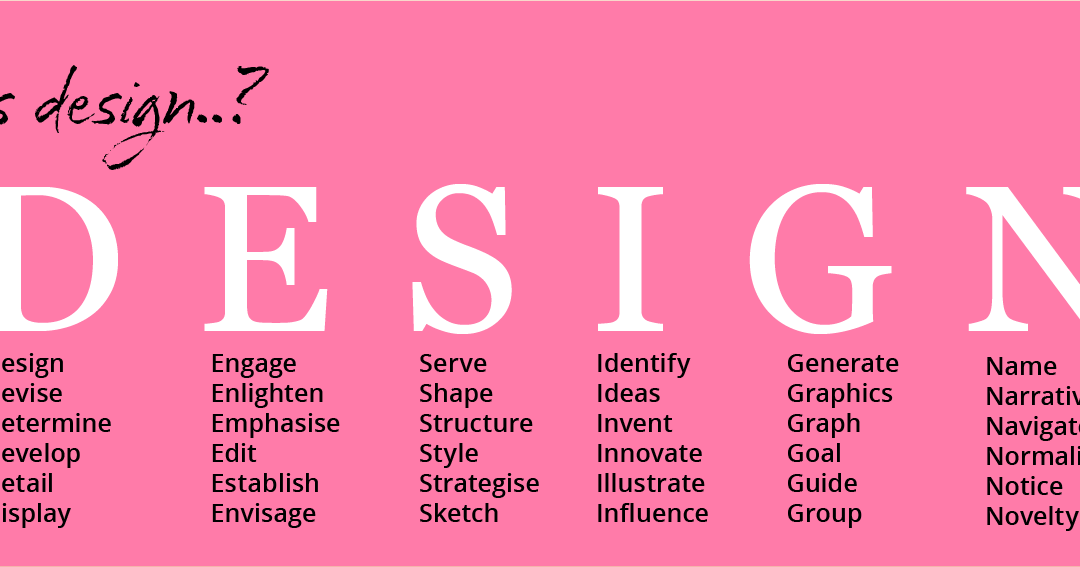

Great, so what is the value of design?

The term “design” has a lengthy and complex history. It originates from the 14th-century word “desinner,” which means to mark or show a sign.

Over time, design has become associated with various fields, including art and industry, which has influenced our understanding of the term and how we value it.

As discussed in Part 1, there is no universally accepted definition of design, leading to differing interpretations.

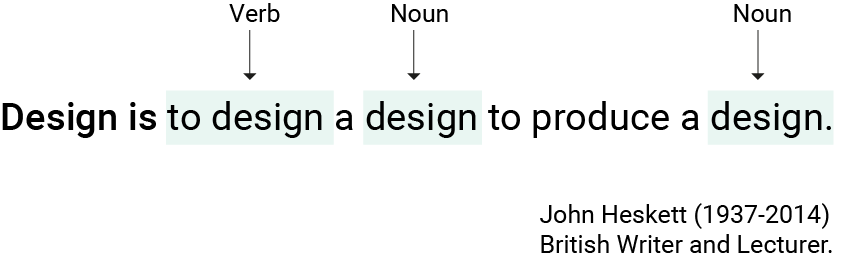

Scholar John Heskett sums up the dilemma beautifully with his clever play on words: “Design is to design a design to produce a design.”

We could say that design and its value extend beyond just aesthetics or functionality.

As Herbert Simon, a pioneer in the field of computer science, put it,

design is what happens when we create a course of action to change an existing situation into a preferred one.

This applies just as much to designing a physical product as it does to designing a user-friendly digital interface. I’ve seen this transformative power firsthand.

Some of the most memorable moments of my career were when I witnessed university students, perhaps studying law, business, or even medicine, take my digital design class and suddenly become inspired by their newfound knowledge.

They didn’t need or want to become designers, but they could see the benefits (the value) of having these design skills in their careers.

Part 3?

Interestingly, as I reach the end of this post, I have realised there is so much still to share on this topic. I must write Part 3!

In that article, I can offer a more in-depth examination of design and its impact on work and the economy.

In the meantime, if you hear the word “design,” perhaps use it as an opportunity to explore, clarify, and build a shared understanding with whoever you are speaking with. When we speak the same language, we can achieve amazing things.

How would you explain design to someone who is unfamiliar with it? Please let me know!

Thank you for reading. I hope you find these words interesting and helpful!

Until next time,

Jan

How can I help?

If we can’t agree on a single, perfect definition of design, how can we ensure we’re all on the same page?

That’s where my research comes in. I’ve spent years exploring this very question, and I’ve developed two tools to help:

- The Handbook for Non-Designers: 65+ ESSENTIAL Concepts

Think of this as your foundation in design and digital literacy. I’ve hand-picked over 65 essential terms, from “design” to “accessibility” to “file formats.” I explain them in plain English. What do these terms mean, why do they matter to you, and how do they impact your work? No jargon, just clarity. Section I is all about design!

- The AAVA Framework: Your Simple Guide to Shared Meaning

Knowing the words is only half the battle. You also need a process to ensure everyone understands them the same way. That’s where AAVA comes in. This four-step framework, born directly from my PhD research, helps you build shared understanding in any conversation:

- A for Accept: we must first accept that we tend to overlook our different interpretations of even commonly used words.

- A for Assumptions: we all have assumptions so it is critical that we remember they are present if we want shared meaning.

- V for Vocabulary: it is always worth checking what different terms mean to your group, especially words we think everyone knows.

- A for Acknowledge: now it is time to identify and document shared meanings, so everyone is clear about what a word means in that instance.

AAVA is not about telling people what to think. It’s a practical, actionable way to cut through the confusion and ensure everyone is working in the same direction.

0 Comments